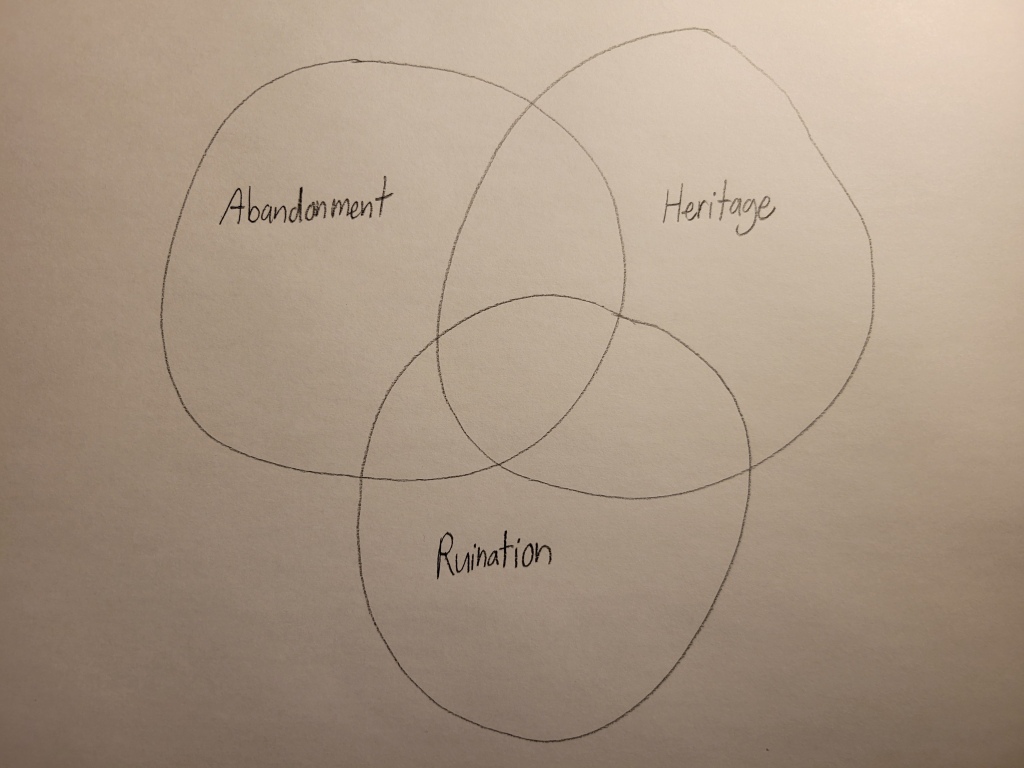

This week we return to my final paper, Beauty in these Broken Stones, and delve into three articles from three different anthropological journals that will be useful for my project. As I’ve talked about here, conceptualizing is the hardest part of any writing project for me. Fortunately, I recently have been captivated by KL’s “bedraggled daisy” metaphor for conceptualizing papers (as discussed in Chapter 5 in her book) and I pretty much have decided to make a daisy (or hardcore Venn diagram) for any large writing project. While it needs refinement, Version 1.0 of my daisy for Beauty in these Broken Stones looks something like this:

The more I read, the petals and petal intersections of my daisy become sharper and sharper, and I find myself getting closer to my research question in the centre. My daisy made it easier to figure out what sorts of articles I wanted to find and annotate: articles on abandonment, ruination, and heritage, ideas that have been percolating in my head this whole time even back when I was planning the original iteration of Beauty in these Broken Stones. Not only did I find several thought-provoking articles with these terms in mind, but I’ve also found full books and book chapters with ideas I want to explore within my petals and petal intersections. I now have a lot of exciting upcoming reading, but without further ado, on with these three articles!

Journal of Material Culture: Article by TE

Through industrial ruins in Great Britain, TE interrogates the normative ordering of the material world and examines how objects in ruins diverge from it. Such objects that have not yet been disposed of are called “waste”, and these objects both attest to the normative order and express an incredible potential of alternate aesthetic and epistemological possibilities. In the normative ordering of the material world, everything has a place and objects are displayed and arranged in certain ways to illustrate a particular point, such as in shop windows and museums. There is no confusion as to what the meaning is, but such ordering restricts interpretive options and thus ensures the domination of certain cultural values. However, when something is abandoned, ruination swiftly follows as there is no more maintenance to uphold the material order and thus the social order. Things fall apart, their material qualities become more noticeable, and new possibilities abound. Not yet disposed of and no longer part of a standard, easily definable object group due to the processes of ruination, people can still interact with ruins, enjoy different aesthetics from their configurations, and make meanings with them.

This article made my brain grow in ways I did not know it could, through TE’s valuation of supposed “disorder” in the material world. Parts of it read like he was granting permission for us to enjoy escaping the regulation of daily life through ruins, and I also appreciated how his vivid descriptions and photographs of industrial ruins in Great Britain even seemed to encourage us to make our escape. By writing in this way, TE not only brought the true materiality of objects into the article, but he also brought people’s experiences into it by pointing out how smooth and controlled many of our spaces and objects are, thus dictating how we sensorially experience them and limiting the material agency of things. Through his vivid illustrations, the reader is invited to escape the regulation of daily life by defamiliarizing the ordinary in the most powerful, sensorial, emotive way possible: the beckoning call of the ruin. While people’s experiences need to be discussed more often in this way, one must appreciate that these “experiential”, anecdotal aspects are not a substitute for rigorous research methodology. Still, they should be discussed more often and I applaud TE for initiating the conversation.

There are no words to describe how thrilled I am to have found this article for Beauty in these Broken Stones. To attempt though, I am delighted to have read about a type of ruin that is not a conventionally aesthetically pleasing ruin. Reading about industrial ruins was relatable to my work, as Lemiez’s sculptures, while works of art, have industrial qualities as they are made of concrete and now have exposed metal frames poking out of them. TE has given me much to think about, including questioning the supposedly desirable outcome of becoming heritage. Lemiez himself wanted his artwork on his homestead to be designated and so protected as heritage by the Manitoba government, and from conversation with the Rural Municipality of Grahamdale it is clear they too are concerned about preventing ongoing weathering and destruction of his sculptures. While these perspectives are legitimate, TE illustrated an important concern of something being designated as heritage: it loses itself, its material agency, and joins a list of “commodified memories” (2005, p.312) that serve people. Through normative ordering, a heritage site means one specific thing, with any other possibilities being obliterated. There is a danger then in designating Lemiez’s homestead as heritage as that would not allow for alternate meanings, thus causing the loss of its curious appeal to visitors. I also wonder if those who make decisions on what constitutes heritage could even wrangle Lemiez’s homestead into heritage, as the homestead already defies the singular meaning scheme through its ruination. In my view, it may be considered too confusing epistemologically in its display and arrangement, and so not heritage. Perhaps with Lemiez’s homestead we should leave it the way it is and let the unique interpretations roll.

Journal of Social Archaeology: Article by ÞP

By exploring two abandoned herring factories in Iceland, ÞP explores the development of equating “intangibility” with all heritage and how this well-intentioned idea ignores the very thingness of ruins. Intangibility is meant to add more inclusivity to the definition of heritage by bringing in non-Western understandings of heritage. However, all heritage being considered “intangible” places the focus on people’s subjective experiences and people connecting with socio-cultural values, which is at the expense of the things themselves as they are denied their concrete, material qualities. Prioritizing subjective human meaning is not new: even for discourse on “tangible” heritage, the reasoning behind protecting things has nothing to do with their materiality and instead is all about meaning and socio-cultural values. The hierarchy that intangibility has helped construct prioritizes our supposed needs over the rights of things; things exist solely to serve us as a resource we are entitled to have. By designating something as heritage and subjecting it to heritage management, a thing loses itself as it can only exist in a certain way. ÞP invites us to consider what is being cared for in these heritage regimes, as well as recognizing it is perhaps “the ruins themselves, in their dynamic state of being, [that] may be the source of their own value and significance” (2013, p.42). ÞP affirms that simply letting something be (the concept of Gelassenheit or “releasement”) allows us to gain a better understanding of things by seeing them in their decay.

When I was reading this article, multiple ideas popped out at me from every page. It was so rapid and exhilarating I was even concerned about getting all of my own thoughts noted down! I admire how ÞP criticizes contemporary ideas of heritage and the intangible orthodoxy while reminding us of the value things have in and of themselves, without people imbuing meanings onto them. I appreciate ÞP bringing in the idea that archaeology in itself is uniquely situated to explore this point. When we find something, we experience this pre-meaning wonder. However, we do not always linger with the unknown and the fascination we have with it. Rather, we feel conflicted between that and our obsession to sort it into something known. Perhaps, following ÞP’s guidance, we should be more open to that sheer sense of wonder given to us by an object and explore the various, perhaps never before travelled, directions it invites us to explore. On a personal level, I can attest to this. During my first archaeological excavation, I unexpectedly found the complete skull of a young adult female bison. The sense of wonder that she inspired in me was profound, and was my initial guide toward many fascinating ideas I later developed more fully.

ÞP has invited me to explore the material world in a myriad of ways particularly relevant to Beauty in these Broken Stones, such as the liminality of modern ruins. The Icelandic herring factories are young in that they are fewer than a hundred years old, yet they are deteriorating. These two ideas conflict: something old is supposed to fall apart and face a kind of “death”, not something young. The fact these factories are young ruins puts them in a liminal space between waste that should be disposed of and history that is worth preserving. The concrete sculptures at Armand Lemiez’s homestead are faced with a similar liminality. They are falling apart yet they are so young, are they waste or are they heritage? Additionally, ÞP’s questioning of subjecting the Icelandic herring factories to heritage management regimes is incredibly relevant to the question of who and what have stakes in those decisions. If Lemiez’s homestead were to be formally conceptualized as heritage, would it lose some of its “cool” factor? For the entire duration of work on the original iteration of Beauty in these Broken Stones, I thought his homestead needed to be understood as heritage to have value and I thought the problem was that “elite” decision-makers did not consider the “folk” perceptions of Lemiez’s art. Understanding his homestead as heritage would reduce its value. As ÞP affirms, it already has intrinsic value as it is, and does not need socio-cultural themes imposed on it. As a result, perhaps the goal should be something different than calling the site heritage.

Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage: Article by SJ

SJ argues how the expert-directed modes of value assessment in heritage do not encapsulate social value. There are many ways to define social value, but SJ defines it as “a collective attachment to place that embodies meanings and values that are important to a community or communities” (2017, p.22). Clearly, social value is about the people and the relevance of a site or a thing to them. While social value is attached to people making meanings out of something, there are other kinds of value that are apparently intrinsic to the things themselves, such as aesthetic value, historic value, and scientific value. While the “heritage sector” finds it hard to measure value, there are many social science methods such as participant observation, focus groups, and qualitative interviews that can be used to ascertain the social value of a place to the people. SJ concludes by providing an example of a project in Scotland that used a rapid version of these ethnographic methods to bring in the knowledge of both heritage experts and concerned communities to include all the different ways heritage can be valued.

Full disclosure: I read this article after the other two, so I was especially attuned to the fact this article does not consider things in their own right. My mind was blown by that idea, and I was somewhat disappointed that the newest article in this group of three did not discuss it. SJ is attempting a corrective to make heritage more relevant to the people, but as I have learned from the TE and ÞP articles, heritage has always been about the people and never the things. SJ’s article upholds the supposedly new “people-first” orthodoxy while ignoring that heritage has been about people this whole time. Aesthetic value, historic value, scientific value, and social value are not intrinsic to things themselves, they have always been human-centred and subjective. At most, this article includes more people in understanding how heritage is valued which is a good and necessary step to make, but things themselves are still neglected in these understandings.

So why then did I select SJ’s article? I assure you, there is still relevance for my paper here! An important idea in Beauty in these Broken Stones is that “elite” perceptions trumped “folk” perceptions of art in the provincial government’s decision-making regarding the preservation of Armand Lemiez’s art, and as a result those authorities deemed Lemiez’s work to have no heritage value. I was hoping to gather some more “folk”-centred ideas from SJ’s article, as it is clear the ideas of “elites” and heritage experts dominated in the decisions surrounding Lemiez’s work. While the materiality of things still is not included, at least SJ includes more people. She presents compelling solutions for bringing in the social value that the “folk” have for a place, which will inspire my musings on how Lemiez’s art and homestead could be managed.